Is It Insane to Start a Business During Coronavirus? Millions of Americans Don’t Think So.

The pandemic closed hundreds of thousands of businesses across the country. But now applications for new U.S. businesses are rising at the fastest rate since 2007. Why? A mix of necessity and opportunity.

By Gwynn Guilford and Charity L. Scott

Sept. 26, 2020 12:00 am ET

The pandemic forced hundreds of thousands of small businesses to close. For Madison Schneider, it was a good time to start a new one.

The 22-year-old in Haviland, Kan., opened Lela’s Bakery and Coffeehouse on Sept. 12, naming it after her grandmother. It has been busy every day since, she said. “It just felt like the right thing to do,” Ms. Schneider said.

Americans are starting new businesses at the fastest rate in more than a decade, according to government data, seizing on pent-up demand and new opportunities after the pandemic shut down and reshaped the economy.

Applications for the employer identification numbers that entrepreneurs need to start a business have passed 3.2 million so far this year, compared with 2.7 million at the same point in 2019, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That group includes gig-economy workers and other independent contractors who may have struck out on their own after being laid off.

Even excluding those applicants, new filings among a subset of business owners who tend to employ other workers reached 1.1 million through mid-September, a 12% increase over the same period last year and the most since 2007, the data show.

“This pandemic is actually inducing a surge in employer business startups that takes us back to the days before the decline in the Great Recession,” said John Haltiwanger, an economist at the University of Maryland who studies the data.

Many of these won’t pan out. More than half of new employer businesses fail within five years, he said. What’s more, small-business revenue was down 21% as of mid-September versus January levels, according to data and technology company Womply. “I think most entrepreneurs realize the probability of success is not high,” Mr. Haltiwanger said. “The question is: Are they jumping on market opportunities that have emerged rapidly given the current environment?”

The pace of new launches comes amid a wave of business closures, which created an unusually large void for new entrants to fill. The U.S. lost more businesses during the first three months of the crisis than it normally does in an entire year, said Steven Hamilton, an economist at George Washington University. In addition, business applications are growing at nowhere near the pace needed to keep up with the 700,000 firms that Mr. Hamilton estimates will be lost this year.

Spending is picking up as cities and states lift restrictions on everything from restaurants to retailers, leading to a rush of activity that had been on hold in the early months of Covid-19. At the same time, the continuing spread of the virus has led to a more sustained shift in consumer behavior than in previous downturns. That has wiped out revenue streams for existing businesses, but also opened up new markets for upstarts.

Another lift may be coming from personal savings rates, which are around three times as high as they were during the last recession, and home prices that remain aloft across most of the country. Nearly 90% of firms depend on an owner’s personal credit score to secure loans, according to a survey by Federal Reserve regional banks. More than half had relied on funds from personal savings, friends or family to support their business at some point in the last five years, the report found.

New-business applications began to pick up in June, likely fueled in part by a change in the tax calendar. After the government postponed tax-filing deadlines from April to July, it pushed back the rush of new-business applications that typically comes in March. As states eased restrictions in May and June, entrepreneurs who had shelved plans during the extreme uncertainty began to move ahead.

The jump may be one sign that the pandemic is speeding up “creative destruction,” the concept popularized by economist Joseph Schumpeter in the 1940s to describe how new, innovative businesses often displace older, less-efficient ones, buoying long-term prosperity.

Even though new businesses inevitably start small, they are a critical engine of job creation. Startups have historically accounted for around one-fifth of job creation, according to Mr. Haltiwanger’s research. More than half of new jobs come from the fastest-growing existing firms, most of which are relatively young companies, he said. Firms with fewer than 500 employees accounted for nearly half of private-sector employment in 2017, according to the Census Bureau.

The 2007-09 recession and the anemic expansion that followed are a reminder of how crucial that engine is. The sluggish pace of new- business creation in years after the recession officially ended contributed to a slow recovery and unusually high unemployment.

Despite widespread fears in the spring that venture-capital investment would dry up, deal activity fell just 6% in the first half of 2020, compared with the same period of 2019, according to a new analysis by Ian Hathaway, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution think tank.

“As the crisis set in, everyone was holding their breath. Then, especially in knowledge-intensive industries, people realized life will go on,” said Mr. Hathaway. “We had a contraction and mass layoffs, but GDP was down 9%, not 50%. It was not as large as people thought.”

Here is a deeper look at eight people who risked their futures on the launch of a new business during one of the worst downturns since the Great Depression. For many it meant trying on new identities and forging new lives.

The Baker

Necessity motivated Ms. Schneider’s gamble. She graduated from college in May, and wanted to work as a worship leader in a church before bans on in-person services scuttled her plans. When a popular coffee shop in town shut down, she decided to reach out to the previous owner to inquire about purchasing the business. “It was way out of my price range,” she said.

Renting the commercial space, however, was much more affordable: just $350 a month. So, she decided to chase her dream of opening a bakery. Ms. Schneider took about $8,000 from her personal savings to finance the startup costs and secured the inexpensive lease in August. Her parents lent her the money to buy an espresso machine. Local residents helped her paint the tin ceiling tiles and pull up old carpet before Lela’s Bakery and Coffeehouse opened this month.

“It all happened very quickly and was really crazy,” Ms. Schneider said. She plans to eventually bring on employees so she can expand her offerings beyond cookies, muffins and cinnamon rolls, and begin hosting special events.

The App Creator

Ileana Valdez saw an opportunity after a sign-up sheet she designed and posted as a joke in a Facebook group for college-related memes received thousands of responses from homebound students. Ms. Valdez and her brother, Jorge, spent a frantic weekend in their childhood home in Dallas, transforming the joke into a functioning dating website for college students. “There was no plan in any way to monetize it or turn it into a startup project, but because there was so much demand, we had to deliver a good product,” she said.

The result, which they dubbed OKZoomer, is a dating platform without profile pictures that now has 20,000 users. New users sign up with their college email addresses, and take a personality quiz, which the OKZoomer algorithm uses to match them with other students from their school.

The fledgling company has since hired six employees to launch the OKZoomer mobile app, and is fielding inquiries from interested venture capitalists, said Ms. Valdez, 21, who is in the final year of earning a computer science degree at Yale University.

“OKZoomer started overnight as a meme, like ‘Missed your last chance to shoot your shot? We’ll help you with our dating algorithm,’” she said. “But it blew up.”

The Fitness Founder

Danielle Payton watched her publicist business wither in March, as fitness studios, a core client base, had to close to comply with shelter-in-place orders. In the weeks that followed, she noticed fitness instructors holding free classes on Instagram Live. “They were giving away their livelihood,” she said. “Free is not sustainable. Our haircuts aren’t free, our rent isn’t free…Nothing is free.”

In response, Ms. Payton, who lives in Miami, Fla., launched Kuudose, an online workout-class platform, with co-founder Rachel Siegel in mid-June. “Fitness should be affordable and accessible to all, but everyone needs to make a living,” she said. The trainers on Kuudose receive monthly commissions for the members they bring to the platform, Ms. Payton said.

Kuudose gives customers access to about 200 short workout routines recorded by professional trainers in their homes for $9.99 a month or $99 for a year. The company has signed up 550 customers so far, Ms. Payton said. “We’re really looking at this as more of a long-term play,” she said. “We’re using the pandemic as the steppingstone to really launch us.”

The Mask Maker

Janizze Masacayan was a nursing home director in Monterey, Calif. when the pandemic hit, placing her at the center of a national health-care crisis while she wrestled with a child care crisis at home. She and her husband had no one to watch her 3-year-old son, who was now home from school due to government stay-at-home orders. “[My supervisor] asked me, ‘Do you want to quit? Because we need you here,’” she said. “So I just quit.”

To offset the loss of income, Ms. Masacayan decided to try making reusable masks. “As a little kid, my grandma taught me how to use the sewing machine, so I thought, ‘Why not make masks for my family,’” she said.

Eventually, she decided to open an Etsy shop and sell her masks to others. She now has a stand-alone website called Jellybean Boutique, and makes customized masks for a local hotel.

Ms. Masacayan said she wants to expand her products to make her business more sustainable, so she won’t have to work outside of the home. “It’s been really great staying at home and being able to take care of my son,” she said. “It’s just very fulfilling for me.”

The Bike Mechanic

Ian Oestreich realized by early March that the coronavirus meant his days as a fitness trainer were numbered. So he began hawking his knack for fixing bikes. It paid off a few weeks later, when the gym where he worked in Madison, Wis., laid him off, and he began pursuing his idea of creating a mobile bike-repair shop.

After investing about $1,000 of his savings in tools and equipment, Mr. Oestreich launched Backyard Bicycles in April, camping out in friends’ yards around Madison and spreading word of his itinerary via social media.

“This model would only work on the weekends in the prior world,” said the 26-year-old. “Now people are available between Zoom calls. Every day of the week is like a weekend.”

Soon he was putting in 10-hour days, fixing as many as 18 bikes daily. When the gym that laid him off offered his job back in June, he declined—he was earning more running Backyard Bicycles than he would have as a trainer.

“It’s honestly kind of unfathomable,” he said. “It feels like I built a rocket and lit it—and now I’m just holding on to the tail and waiting for it to fizzle out at the end of the season.”

The Chef

Nic Bryon was a sous chef in Tampa, Fla. who lost his job when the restaurant where he worked closed. During his first week of being unemployed, he joined forces with his brother, Greg, to start development on a local meal-kit delivery service called Pasta Packs.

The concept itself is simple: the brothers offer a handful of fresh pasta dishes that arrive packaged with detailed instructions on how to reheat them to achieve a restaurant-quality meal. “You just need to be able to boil a pot of water,” Nic said.

While Nic developed the recipes, Greg, who is a photographer and designer, worked on branding concepts and taking photos of the completed dishes. Pasta Packs initially launched on Instagram, with their first customers being friends. From there, the brothers started a website and began to expand their customer base.

Nic wakes up at 6 a.m. every morning to do grocery shopping for the day’s orders. Then he spends the rest of the morning making the pasta, sauces and other accompaniments, before packaging everything. Nic and Greg said they are currently testing options to ship outside of Tampa.

The Bookseller

Leigh Altshuler always loved bookstores. She even worked at one, spending several years as the communications director for the Strand Bookstore, a well-known independent bookseller in Manhattan.

But it wasn’t until after she lost her job in immersive theater in March that she began thinking of opening her own used bookstore in New York. “I was thinking of all of the things that would make me feel motivated to go back to work, things that I love,” she said.

Ms. Altshuler, 29, is using her own savings to open her shop, getting plenty of other help from her boyfriend, neighbors and friends in the form of book donations and spare hands. She aims to open near the end of October.

“If somebody asked me what I wanted to do when I was little, I probably would’ve said I wanted to have a bookstore, but in New York it never felt like it was a good time to open your own business,” she said.

Some people have questioned whether now is the right time for her to open a retail store. “I may as well just do something crazy and follow my dream,” she said. “And if it doesn’t work now, when will it?”

The Therapist

Joyre Montgomery wanted to start her own therapy practice once she received her master’s degree in 2015. It took a pandemic for her to act on it.

She had a job as a school-based therapist in Chattanooga, Tenn., but that looked uncertain as schools closed and governments enforced lockdowns. The pause gave her the time to focus on what it would take to become a business owner. With new mental-health challenges to confront and a shift to virtual therapy, it seemed like the right time to start her new practice.

Ms. Montgomery created a plan in April and May and by June had completed the requirements to become a licensed clinical social worker. The catalyst that prompted her to open in July was the willingness among insurers to cover a broader range of telehealth visits. Ms. Montgomery got approval from companies to accept insurance in a fraction of the time it would normally take, she said.

She saw her first client on July 13 and now has nearly 60, an unexpected growth for Ms. Montgomery. “I was very shocked,” she said. “It’s almost at a point where I have to say I’m not accepting new clients.”

—Francesca Fontana and Derek Hall contributed to this article.

Write to Gwynn Guilford at gwynn.guilford@wsj.com and Charity L. Scott at Charity.Scott@wsj.com

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Appeared in the September 26, 2020, print edition as ‘Rising From the Pandemic’s Destruction: A Million New Businesses.’

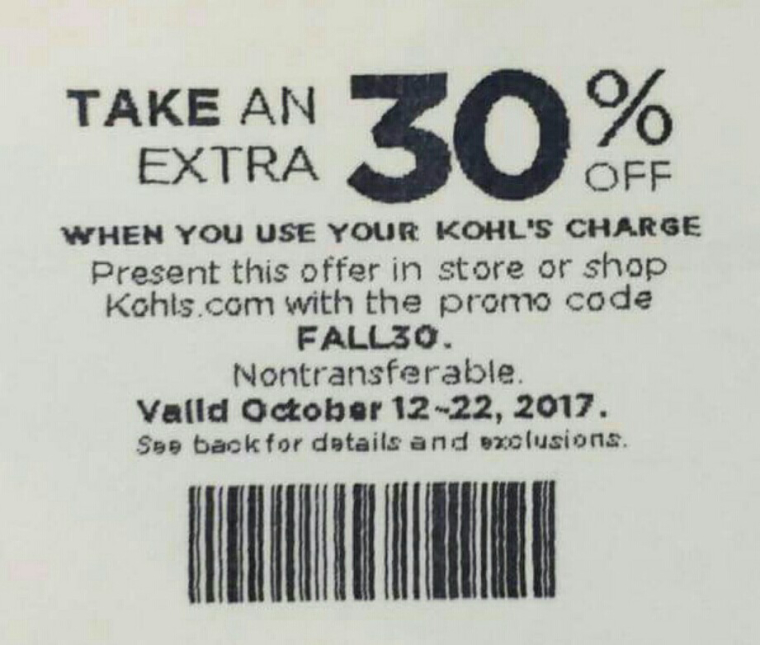

PUMPKIN30).

PUMPKIN30). 20OFFSHOES — 20% off shoes (department-specific %-off)

20OFFSHOES — 20% off shoes (department-specific %-off) MENSTYLE10 — $10 off $50 men’s (department-specific $-off)

MENSTYLE10 — $10 off $50 men’s (department-specific $-off) SAVE30NOW — 30% site-wide (general %-off, calculated last)

SAVE30NOW — 30% site-wide (general %-off, calculated last) SHIP4FREE — free S/H

SHIP4FREE — free S/H = Lowest price of the season

= Lowest price of the season

promotions:

promotions: AUTUMN20

AUTUMN20 CATCH15OFF

CATCH15OFF SERVICE

SERVICE CHEERS

CHEERS AUTUMN15

AUTUMN15 NOVMVCFREE

NOVMVCFREE Mystery Code, valid with any tender, no minimum $

Mystery Code, valid with any tender, no minimum $ FRIENDS25

FRIENDS25 CUDDLDUDS10

CUDDLDUDS10 SHINE20

SHINE20 SHOE10 (unverified)

SHOE10 (unverified)

promotions:

promotions: DADSDAY

DADSDAY

SUNNY25

SUNNY25 STYLE20

STYLE20 DAD10

DAD10 rating

rating promotions:

promotions:

promotions:

promotions:

FRIEND25

FRIEND25 SAVESPRING

SAVESPRING SAVE

SAVE LUGGAGE50 (exp. 10/21/2017)

LUGGAGE50 (exp. 10/21/2017) HOME10 (exp. 10/22/2017)

HOME10 (exp. 10/22/2017) TOY10 (exp. 10/22/2017)

TOY10 (exp. 10/22/2017) 50 Bonus Yes2You Points when you download and sign-in to Kohl’s mobile app. (One-time bonus, for first-time download.)

50 Bonus Yes2You Points when you download and sign-in to Kohl’s mobile app. (One-time bonus, for first-time download.) 15% Senior Discount (@60 yrs.) every Wednesday, in-store only, I.D. required, stackable with $-off promos, Kohl’s Cash, Y2Y rewards, and promotional gifts

15% Senior Discount (@60 yrs.) every Wednesday, in-store only, I.D. required, stackable with $-off promos, Kohl’s Cash, Y2Y rewards, and promotional gifts

!

! BOOKGIFT17 at checkout to qualify.

BOOKGIFT17 at checkout to qualify. promotions:

promotions: SAVEBIG

SAVEBIG

15% Senior Discount (@60 yrs.) every Wednesday, in-store only, I.D. required, stackable with $-off promos, Kohl’s Cash, Y2Y rewards, and promotional gifts

15% Senior Discount (@60 yrs.) every Wednesday, in-store only, I.D. required, stackable with $-off promos, Kohl’s Cash, Y2Y rewards, and promotional gifts UPCOMING PROMOTIONS:

UPCOMING PROMOTIONS: INTIMATES10

INTIMATES10 ANTICIPATED PROMOTIONS: (based solely on 2017 promotions)

ANTICIPATED PROMOTIONS: (based solely on 2017 promotions) promotions:

promotions: SHOE20

SHOE20 SAVE25

SAVE25

DAD10

DAD10